Daniel Barabander

Hourglass Markets: On Crypto, Cross-Border and Beyond

We are actively hiring on our investment team. Apply here if you want to help build the future of crypto.

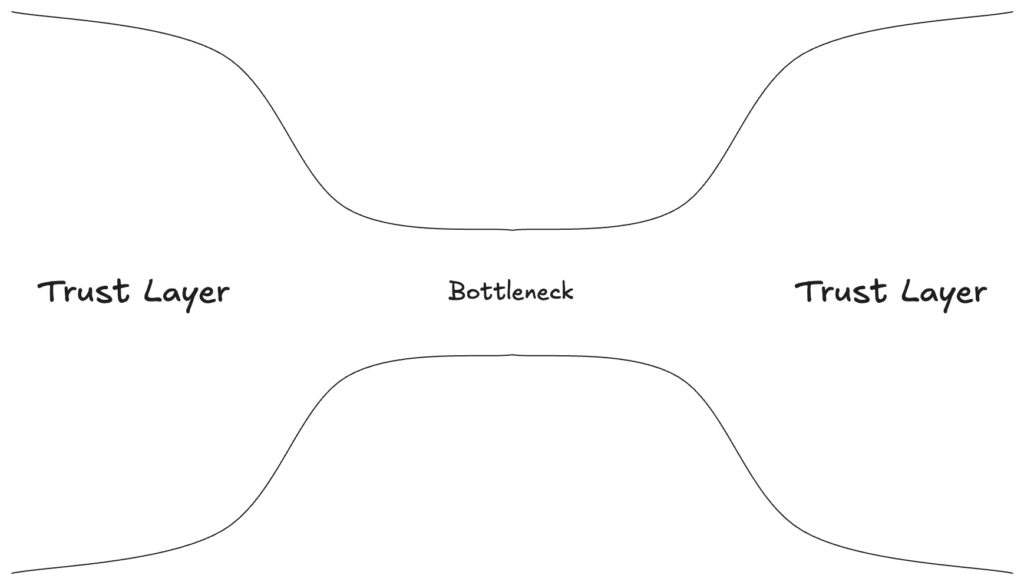

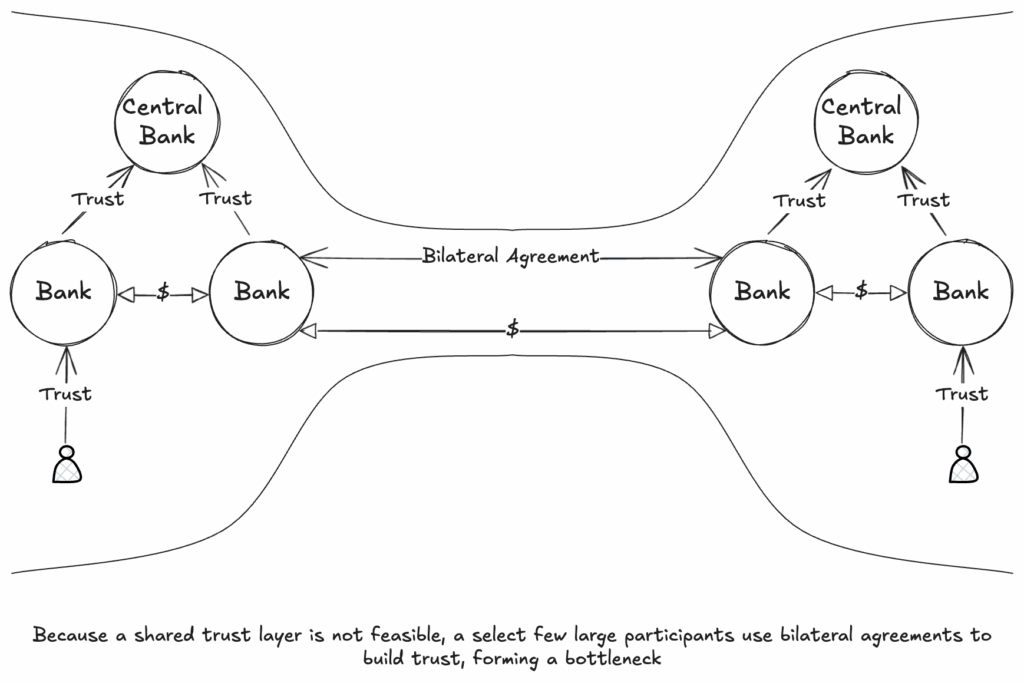

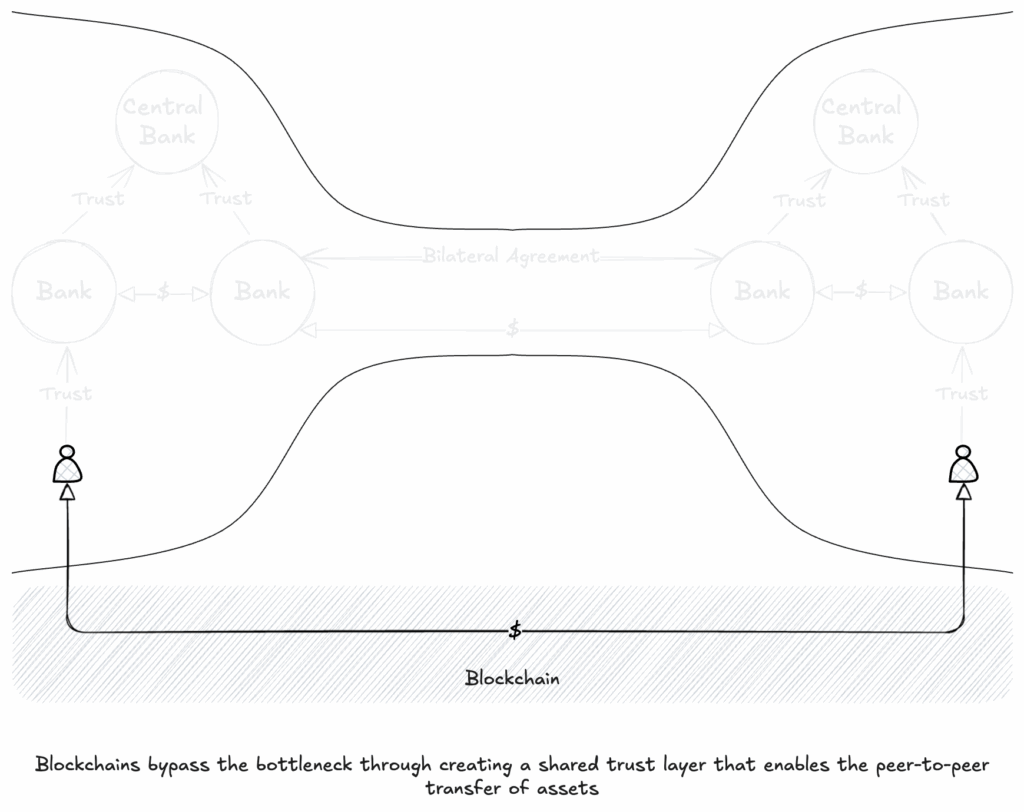

One of crypto’s greatest opportunities is to disrupt what I call hourglass markets — situations where value must travel from one trust layer to another but can only do so through a narrow bottleneck of intermediaries. While these markets can form anywhere, they are especially common in cross-border transactions, where political sovereignty prevents countries from merging their domestic trust layers into a single global trust layer.1

The best place to see these dynamics is in payments.

Imagine trying to pay for groceries by handing the cashier a personal IOU for $50 payable in 30 days. You’d be laughed out of the store. The fundamental issue is settlement risk: You are taking the groceries now while promising to pay later. Because the grocery store doesn’t know whether you will fulfill your obligation, it will not accept your IOU as payment.

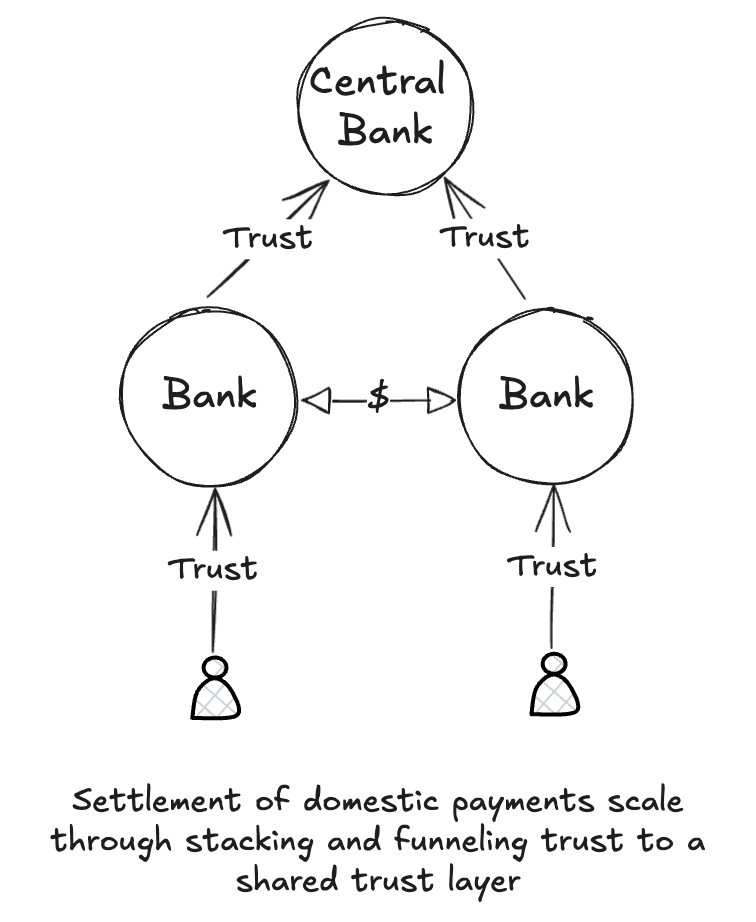

But if both you and the supermarket have an account at Bank A, you can now transfer value much more easily. This is because you both trust Bank A, so when it updates its ledger to debit your account $50 and credit the supermarket’s account $50, each participant recognizes the transaction as settled. We have solved the settlement problem by stacking and funneling trust one layer up to a shared trust layer, Bank A.

The problem is reintroduced when participants have different banks. Bank A does not trust Bank B’s ledger for the same reason the supermarket does not trust yours. But we solve this, again, through stacking and funneling trust to another shared trust layer, the central bank. We give Bank A and B accounts at a government-run central bank; to accomplish a cross-bank transfer, the central bank debits Bank A’s account and credits Bank B’s account.

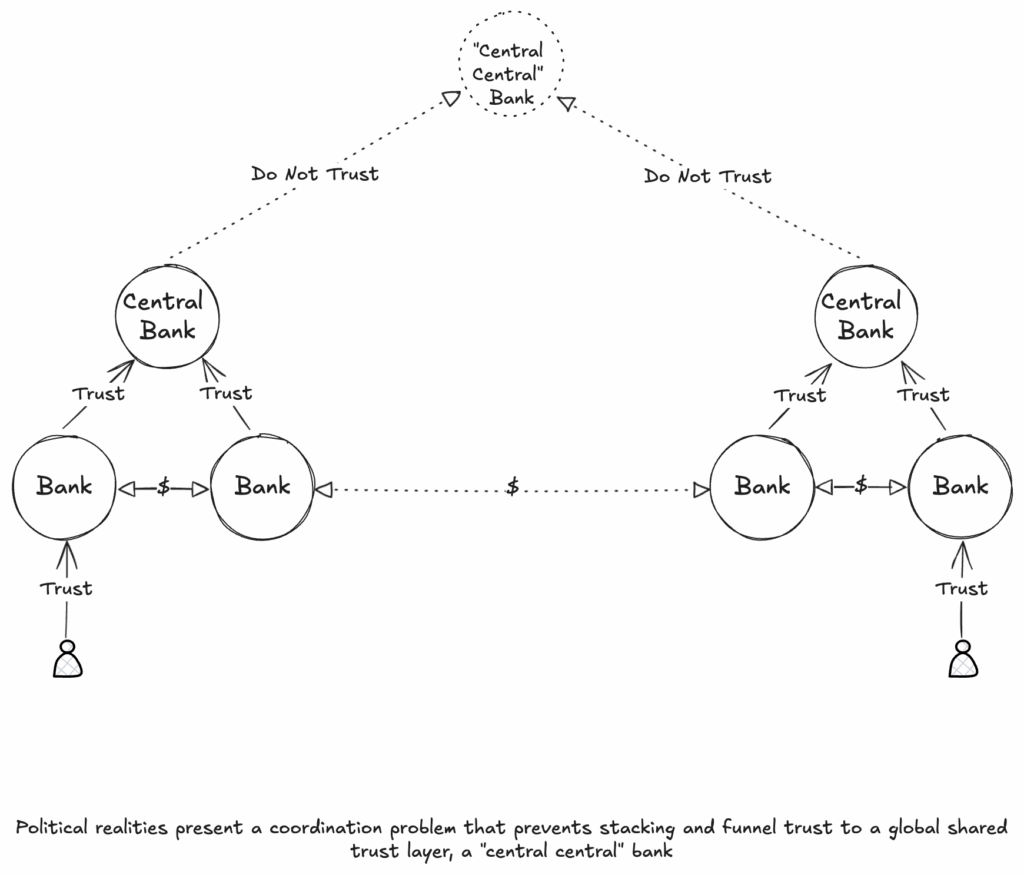

As we can see, the default way to scale payments is by stacking and funneling trust from disjointed trust layers onto the same centralized trust layer. But when things go cross-border, we are faced with a fundamental coordination problem that makes stacking and funneling infeasible. There is no “central central” bank to settle payments across borders because no country trusts another country to run a global central bank; each nation maintains its political and economic sovereignty (particularly because each sovereign issuer is the source of truth with regards to its own currency).2 Our settlement problem is reintroduced.3

Because banks in different jurisdictions don’t share a common settlement layer, they instead rely on bilateral agreements to bridge the gap between disjointed trust layers. Effectively, Bank C in Argentina must open an account at Bank B in the U.S. But because Bank C does not trust Bank B, it must use legal contracting to build this trust so that transfers on Bank B’s books are treated as final settlements.4 These bilateral agreements are costly, requiring disclosures, AML/CFT requirements, collateral, and audits. The institutions that provide this service are called correspondent banks, because they have a correspondent account at each other’s bank.

Only a handful of banks are large enough to command sufficient trust5 and operate at the scale needed to absorb the high costs of these agreements.6 Indeed, as of 2019, just eight banks handle over 95% of euro-denominated cross-border transaction volume. These select few banks hold an oligopoly over this interoperability function, forming an anti-competitive bottleneck that constrains the flow of funds between trust layers. Take remittances, a nearly $1T market: the average cost of remittance is about 6%, and the average time to delivery is often a full day or more, largely due to inefficiencies created by this bottleneck. It’s an hourglass market.

Enter crypto. Crypto solves the settlement problem7 by creating a shared trust layer all participants recognize as valid through the creation of a ledger controlled by no one.8 A token on a blockchain functions like a digital bearer asset: whoever controls the keys is recognized as the owner. This democratizes access to holding and transferring value because we do not need to trust the sender of the asset to settle the transaction. As a result, participants can transfer assets peer-to-peer.

This is the real reason stablecoins have so much product-market fit in cross-border payments. By enabling the peer-to-peer transfer of dollars, crypto allows participants to bypass the bottleneck in this hourglass market, making cross-border payments far more efficient.9

While in some sense this is “Crypto 101,” this framing allows us to zoom out to see that hourglass markets form naturally, even inevitably, in cross-border transactions. This is because principles of political sovereignty consistently present a coordination problem that prevents separate countries from merging disjointed trust layers. Wherever we see this pattern, crypto can disrupt it by bypassing the inevitable bottleneck.

Equities are another example of a cross-border hourglass market. The ownership of public equities looks a lot like our banking system. In the U.S., we stack and funnel trust through brokers and custodians, and then again up to a central securities depository (CSD) called the DTCC. Europe follows a similar model, with trust ultimately stacking up to its own clearinghouses like Euroclear in Belgium and Clearstream in Luxembourg. But just as no global central bank exists, a global CSD is infeasible. Instead, these markets are bridged through a handful of large intermediaries using costly bilateral arrangements across trust layers, forming an hourglass market. The result is, predictably, that cross-border equity transactions remain slow, expensive, and opaque. Again, we can use crypto to democratize ownership and bypass the bottleneck to allow participants, regardless of their geography, to directly own these securities.

Beyond Cross-Border

Hourglass markets are everywhere once you know how to look for them. In fact, even within cross-border payments, there are arguably two hourglass markets: the one I focus on in this piece — the movement of money across borders — but also the exchange of currencies.10 For similar reasons, FX markets form an hourglass, with a small club of global dealer banks — connected through a dense web of bilateral trading agreements and with privileged access to settlement systems like CLS — sitting at the bottleneck between disjointed national currencies. Projects like OpenFX are now using crypto to bypass this bottleneck.

While cross-border transactions are the lowest-hanging fruit for identifying hourglass markets, these markets are not geographically specific. They can emerge wherever the right conditions exist. Two in particular stand out:

- Assets with utility across layers. Hourglass markets require assets with utility across layers; otherwise, participants have no reason to transfer them and no bottleneck will form. For example, the Kindle Book Store and Apple Book Store could be seen as disjointed trust networks — each issues IOUs for digital book licenses, but neither has an incentive to make its IOUs compatible with the other’s network. Because a Kindle book has no utility on Apple, there is no reason to transfer it across layers. Without that utility, no intermediaries emerge to facilitate movement, and no hourglass market forms. By contrast, assets with broad or universal utility — such as money or instruments of speculation — are far more likely to.

- Regulatory fragmentation. We can describe cross-border bottlenecks as the fragmentation of trust layers imposed by different regulatory regimes, and the same effect can also arise within a single jurisdiction. For example, in domestic securities markets, cash typically settles through RTGS systems while securities settle through CSDs. The result is costly coordination through brokers, custodians, and other intermediaries — a domestic hourglass that BIS estimates costs banks $17–24 billion a year in trade processing.

In conversations for this piece, I heard about a range of other potential hourglass markets, from syndicated loans, commodity futures, carbon trading, and more. Even within crypto, there are arguably many, such as fiat-to-crypto on-ramps/off-ramps, certain bridging between blockchains (e.g., wrapped BTC), and interoperability among different fiat-backed stablecoins. The builders who spot these hourglass markets will be best positioned to use the principles of crypto to outcompete systems rooted in bilateral agreements.

1. h/t to the excellent article, “Trust Bridges and Money Flows” by the IMF for this superb framing of “trust layers.”

2. While the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) is sometimes described as a “central bank of central banks,” it does not function as a global settlement authority. It cannot issue a universal reserve asset or provide final settlement across disjointed national banking systems.

3. While I frame this as a problem of trust, there are also practical and regulatory reasons why settlement systems remain domestically limited. Even if banks across borders trusted one another, the operational burdens of participating in RTGS systems and the local restrictions imposed by regulators would still fragment payments along national lines.

4. In reality, Bank B and C would much more likely have a bilateral agreement with a US G-SIB (e.g., JPM), who would sit in between them (and therefore be in the middle of the funnel).

5. All else equal, other banks are going to want a correspondent bank whose liabilities are extremely close to risk-free. This means being big enough to benefit from a “too big to fail” backstop.

6. Since the global financial crisis, correspondent banking relationships have been in steady decline, with many jurisdictions reporting significant losses in the number of active relationships and growing concentration among a small group of banks. This is due to a variety of factors, including heightened AML/CFT requirements, stricter regulatory and compliance standards, profitability concerns, and banks’ efforts to de-risk by exiting higher-risk markets.

7. There is still trust that the issuer of the token will redeem the dollar (e.g., redemption trust). But the core point is that crypto solves trust issues associated with the settlement problem.

8. To be clear, a blockchain is still a trust layer — but the trust comes from the fact that no single party controls it, which is why it’s described as “trustless.”

9. Peer-to-peer transfer describes the movement of assets, but regulatory regimes can still impose an hourglass market on top. For example, a country could require that stablecoins be accessed only through a handful of licensed providers, creating a bottleneck even though peer-to-peer transfer of the assets is technically possible.

10. Even when using stablecoins, we bypass the correspondent banking bottleneck but introduce a new hourglass market: on- and off-ramps. And in the case of the USDC/USDT “stablecoin sandwich” between two non-USD currencies, we actually create two FX bottlenecks — for example, converting local currency 1 into USDC, and then USDC into local currency 2. That’s why I’m so excited about local currencies onchain: They allow us to sidestep these bottlenecks.

Thank you to Jordan Bleicher, Ethan Buchman (Cycles), Dave Taylor (Etherfuse), cush (Odisea), Chuk Okpalugo (Paxos), Andrew MacKenzie and Tom Rhodes (Agant), Prabhakar Reddy and Karan Shah (OpenFX), Michael Sonnenshein (Securitize), Austin Adams (Whetstone), Clayton Blaha, Elijah (Neutron), Charlie (Felix), David Phelps (JokeRace), Austin Campbell (Zero Knowledge Group), Nick Grossman (USV), Sam Broner (a16z), Larry Sukernik (Reverie), Shawn Lim (Artichoke), and Regan Bozman (Lattice) for their thoughtful feedback and discussion on this article.

Thank you to my superb colleagues Jesse, Jake, Alana, and Jack for invaluable discussions and debate on this topic.

All information contained herein is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any investment and should not be used in the evaluation of the merits of making any investment decision. It should not be relied upon for accounting, legal or tax advice or investment recommendations. You should consult your own advisers as to legal, business, tax, and other related matters concerning any investment. None of the opinions or positions provided herein are intended to be treated as legal advice or to create an attorney-client relationship. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by Variant. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, Variant has not independently verified such information. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by Variant, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Variant (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for Variant to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://variant.fund/portfolio. Variant makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. This post reflects the current opinions of the authors and is not made on behalf of Variant or its Clients and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Variant, its General Partners, its affiliates, advisors or individuals associated with Variant. The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without being updated. All liability with respect to actions taken or not taken based on the contents of the information contained herein are hereby expressly disclaimed. The content of this post is provided “as is;” no representations are made that the content is error-free.