Li Jin

Progressive Ownership: A Model for Application Tokens

We founded Variant on the thesis that the next generation of the internet would transform users into owners through tokenization. Utilizing tokens as a user incentive has worked exceptionally well for bootstrapping infrastructure networks like Bitcoin and Ethereum. However, the application layer has yet to see a proven model for using tokens to grow networks. Rather, there are many examples where distributing tokens has actually impeded sustained growth and retention by attracting more speculators and mercenaries than genuine users, obfuscating product-market fit.

Because of these failures, many dismiss the use of tokens for applications as a category error, but we don’t see it that way. Instead, we believe the answer is to keep iterating token design toward a more bottom-up and opt-in ownership distribution model that we call “progressive ownership.” This approach focuses on deepening loyalty among users of applications with product-market fit.

In this framework, we outline previous eras of token distribution mechanisms—PoW mining, ICOs, and airdrops—and their key lessons and problems. We then propose high-level steps and tactics for a new token distribution model, which we believe could sustainably grow applications with early product-market fit. By applying this playbook, apps can leverage user ownership to deepen existing user loyalty, paving the way for further growth and retention.

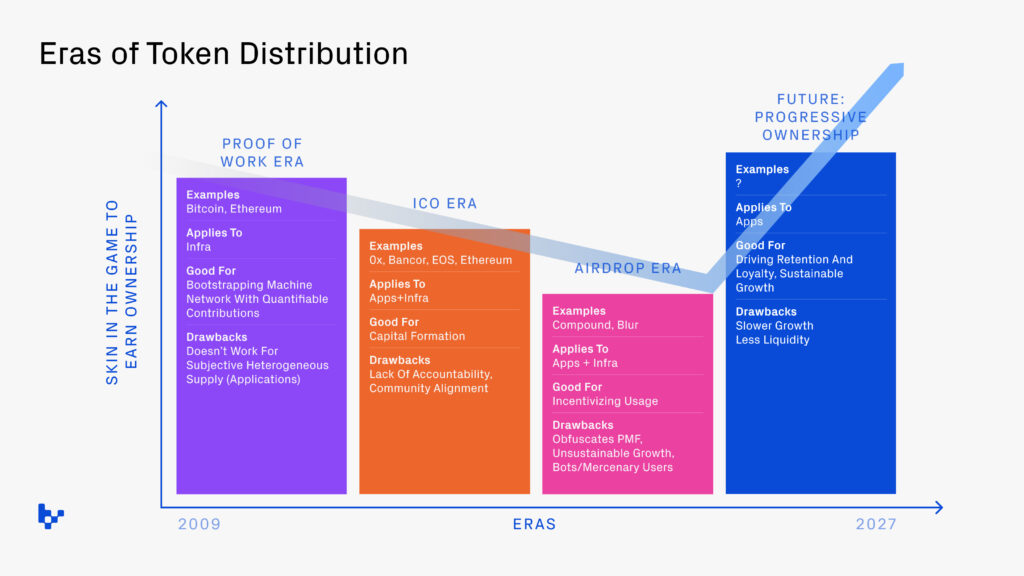

Three eras of token distribution

Crypto has undergone three major eras in token distribution models:

- Proof of Work (2009–present): hardware formation

- ICOs (2014–2018): capital formation

- Airdrops (2020–2023): bootstrapping usage

Each model lowered the skin in the game for participants while broadening access, so each era naturally coincided with a new wave of growth and development in the space.

- Proof-of-work era (2009–present)

Bitcoin pioneered the idea that a permissionless network could be operated by anyone willing to run software on their machines (“mining”) in exchange for tokens representing ownership in the network. Miners who devoted more computational power had a greater chance of earning rewards, fostering professionalization that required meaningful investment in computing resources.

The PoW era showed token incentives can be very effective at bootstrapping supply in networks where contributed value can be quantified, e.g. computing power. Critically, the capital asset (hardware) is distinct from the financial asset (BTC), which forces miners to sell the financial asset to cover their costs. As specialized hardware became a necessary cost, miners had to have more skin in the game, but this dynamic also edged out ordinary users.

- ICO era (2014–2018)

The ICO (initial coin offering) era marked a significant departure from the proof-of-work distribution model: projects raised capital and distributed tokens by selling them directly to prospective users. This approach theoretically allowed projects to bypass intermediaries like VCs and bankers and reach a broader range of participants who could share in the upside of products and services they would use.

The promise of the model attracted entrepreneurs and investors and incentivized a wave of speculative interest. In 2014, Ethereum was partly bootstrapped through an ICO, serving as a blueprint for many projects in subsequent years, including large 2017-2018 ICOs such as EOS and Bancor. But the ICO era was rife with fraud, theft, and lack of accountability; and the failure of many ICO projects, plus intense regulatory scrutiny, brought about its quick decline.

ICOs highlighted the capabilities of blockchains for permissionless, global capital formation. But this period also underscored the need for more thoughtful token design and distribution models that prioritize community alignment and long-term development, not just capital provision.

- Airdrop era (2020–2023)

In 2018, an SEC official suggested that BTC and ETH were not securities because they were “sufficiently decentralized.” In response, many projects designed tokens that incorporated governance rights and retroactively distributed them broadly to their users, with the aim of achieving sufficient decentralization.

Unlike ICOs, which distributed tokens for monetary investment, airdrops rewarded users for their historical usage. The model kicked off “DeFi Summer” in 2020, which popularized liquidity mining (supplying liquidity in a financial marketplace to earn tokens) and yield farming (selling the earned tokens as short-term gains).

While airdrops were a shift toward a more user-centric and community-driven ownership distribution model, very little skin in the game was required from users, and most airdrops resulted in users converting ownership to income by selling the majority of their tokens upon receipt.

Many projects leveraged airdrops before establishing true product-market fit. Tokens drew in bots and short-term, mercenary users driven solely by incentives, rather than putting ownership in the hands of users who were aligned with the long-term success of the project. The rush to claim and sell tokens obfuscated signals around product-market fit and contributed to boom/busts in prices.

A number of projects that rushed out tokens also saw their founding teams step back in an attempt to comply with an ambiguous regulatory litmus test of sufficient decentralization. That left decision-making to governance referendums that most tokenholders did not have the time or context to fully understand. Before reaching product-market fit, and even afterward, projects need founders to continue to iterate quickly. Airdrops often proved to be a mismatch between growth strategy and a startup’s organizational execution.

We think the primary lesson from the airdrop era is that the pursuit of sufficient decentralization guided many projects away from product-market fit. Instead, token distributions should be more thoughtfully targeted with a heavier weighting to power users, after early product-market fit is validated.

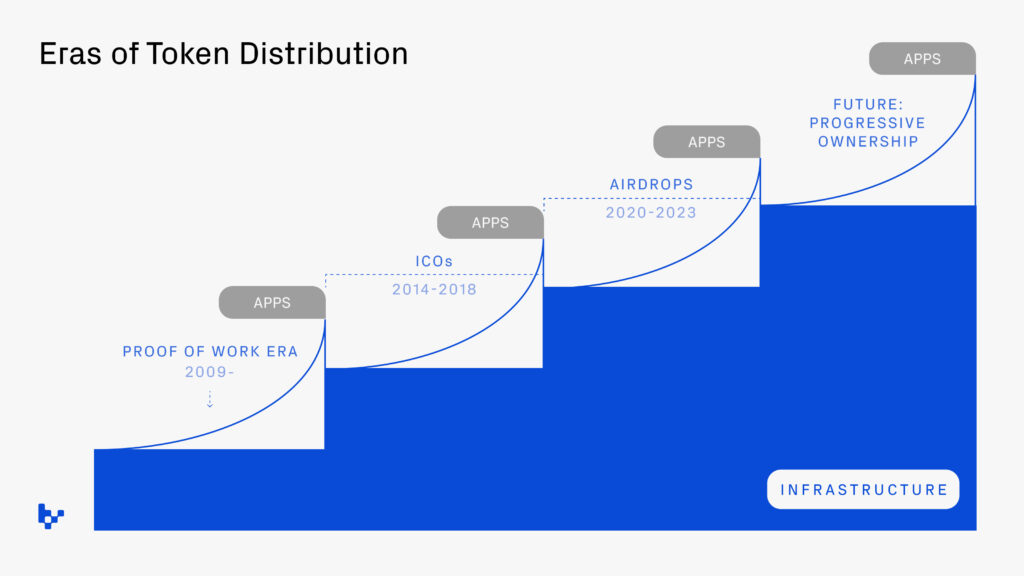

Each era of token distribution spurred growth and development of applications. Credit: inspired by app/infrastructure cycles [USV]

A novel token distribution framework: Progressive ownership

Progressive ownership builds on progressive decentralization, which advised that tokens are not a substitute for product-market fit. This approach employs economic incentives in degrees to increase user loyalty and retention, step-by-step, culminating in ownership. Under this model, users are incentivized with revenue share income (e.g. ETH or stablecoins) but can decide to trade individual income for tokens representing ownership of a proportional share of the community’s revenue.

This has advantages for users, who can move fluidly between income and ownership, with fewer steps than the previous default of converting tokens to income. It also enables them to tune their economic participation to the level of risk and engagement appropriate to their circumstances.

And there are advantages for builders, who can leverage revenue share incentives to drive growth, build loyalty, retain control, and iterate quickly without being distracted by sufficient decentralization. Further, founders can still work toward paths to realizing liquidity via tokens, while trying to mitigate the risks associated with broad, untargeted token distributions.

Progressive ownership is only an option for projects that have early product-market fit and revenue to share. While the current scale of revenue among most crypto projects is relatively small, the list of projects meeting this criteria is growing. Optimism has logged roughly $30 million in revenue year-to-date. MakerDAO accrued $16 million in fees from the protocol in October and has seen 25% compounded monthly average revenue growth in the past year. And ENS (Ethereum Name Service) has generated $1.1 million in revenue in the past month.

Progressive ownership shifts token distributions from an opt-out to an opt-in model, which has the potential to engender stronger loyalty and network effects due to more skin in the game. As committed users level up into ownership, they are more economically aligned with the success of a network and incentivized to encourage others to join, which creates a virtuous growth loop. Users or developers who opt into ownership are more likely to skew long-term, as is the case with startup employees with stock options.

Conversely, in the airdrop model, loyalty can be eroded as most users choose to sell and convert tokens into income, creating downward price pressure. Studies have shown that experiencing losses as a shareholder can induce lower customer satisfaction and loyalty toward the company. By making ownership opt-in, networks can mitigate these boom-and-bust cycles and their ensuing erosion of user goodwill.

The playbook

Progressive ownership involves 3 steps:

- Build products that serve users’ needs

- Use onchain revenue sharing to drive growth, retention, and defensibility

- Allow power users to level up into economic ownership (e.g. trade income for tokens)

- Building products that serve user needs

This is the hardest step. The foundation of the progressive ownership model begins with developing products and services that serve users in novel ways. As Li recently wrote: “Successful startups offer a step-function improvement in enabling people to achieve a core need.”

By meeting these needs, which range from income to esteem, apps can find product-market fit—and even cultivate psychological ownership.

- Using onchain revenue share for growth, retention & defensibility

Projects can employ onchain revenue share models that allow users to share in the success of a product/service, deepening their interest and commitment.

A primary example is Zora’s protocol rewards, which allocate a portion of earnings to creators and developers for driving NFT mints. This approach not only encourages user retention but also bolsters defensibility.

Some projects stop here—and indeed, this is a canonical playbook of web2 companies, ranging from Substack to OnlyFans to YouTube to X/Twitter. Revenue share is a powerful draw and has obvious scaling effects.

But the reason to go further than revenue share is that economic ownership can more meaningfully align users with the long-term success of the platform rather than conditioning them for short-term gains. Users with economic ownership would be more attuned to how their contributions fuel the platform’s growth. This mirrors the age-old Silicon Valley playbook for incentivizing startup employees.

- Allowing power users to level up into ownership

Finally, the most loyal power users can opt into ownership via tokens that comprise both economic and governance rights. This transition is not automatic and passive, but something users choose. For example, the most valuable users as measured by revenue generated could be given an option to either 1) earn revenue share in the form of ETH/stablecoins, or 2) take a proportional token distribution in the project’s native token.

In choosing the latter, a user is trading some of their individual income for a portion of the community’s total income. If the network grows, the community’s income will grow, and the token should enable them to participate proportionally. Further, the token might offer governance over key protocol parameters, such as fee or revenue share variables, to ensure long-term alignment.

There are many more implementation details to work out. (Should users have to stake their tokens to earn platform fees? Should tokens be subject to vesting?) But without getting too deep in the weeds, a few hypothetical examples:

Coming back to Zora, about 1,008 ETH in protocol rewards has been distributed to date. Those rewards are revenue-share splits, mainly distributed to NFT creators who drive minting activity, but also developers and curators. In the progressive ownership model, top Zora revenue generators could choose to claim hypothetical Zora tokens instead of ETH protocol rewards. How many creators and developers would opt to do that? Probably a small percentage, but those who did would have meaningful skin in the game and potentially become even more active and incentivized to grow the network.

Another hypothetical is Farcaster, which charges roughly $7 in annual fees to individual users to store data on the network. Imagine if the protocol shared that revenue with developers building clients that drive attention. Developers could then choose whether to pass that value on to end-users, akin to a rebate. Alternatively, developers could convert a portion of their revenue share into protocol tokens that give them exposure to growth in the ecosystem and governance over key protocol parameters.

Precedent in web2 models of loyalty

The progressive ownership model closely aligns with business researcher James Heskett’s ladder of customer loyalty (2002), which comprises four stages: “loyalty (repeat purchase), commitment (willingness to refer others to a product or service), apostle-like behavior (willingness to convince others to use a product or service), and ownership (willingness to recommend product or service improvements).”

Progressive ownership recognizes that customer loyalty requires ever-deepening levels of psychological ownership. As users ascend the ladder from income to tokens, they might feel an increasing degree of psychological ownership, culminating in more vocal advocacy—acting like an owner of the product and taking on more responsibility for its continued success.

This emotional connection can be nurtured through financial levers (revenue share) as well as product elements (personalized experiences, interactive features, and user input), making users more inclined to become long-term stakeholders.

Leveraging economic ownership to entrench user loyalty also aligns with research from the public equities world, which suggests that stock ownership can boost brand loyalty among existing users. As Li wrote:

A Columbia Business School study found that in a fintech app where users selected certain brands or stores to receive stock from once they shopped there, users’ weekly spending jumped by 40% at those brands… Users intentionally selected their stock holdings and invested time shopping at those brands in order to receive a stock grant.

Transitioning to a new era of token distribution

The progressive ownership playbook represents a significant departure from previous eras of token distribution. Whereas ICOs and airdrops were primarily intended as bootstrapping tools, they often proved ineffective at motivating organic users. As a result, entrepreneurs were often led astray from finding product-market fit.

In the progressive ownership model, revenue sharing spurs growth and entrenches loyalty, culminating in ownership that users proactively choose, ensuring that only the most deeply committed users become stakeholders. This paves the way for a community of dedicated advocates who are invested in the long-term success of the network. While there will likely be unforeseen challenges with this model, it aligns closely with precedent examples of economic ownership enhancing loyalty.

How progressive ownership relates to the compliance framework of sufficient decentralization is the subject of another post. The industry will need novel compliance arguments that enable teams to continue building great products while leveling up power users through ownership. That is work we plan to push forward at Variant.

Innovation in token distribution has catalyzed spurts of new growth and development in the ecosystem, and the playbook is very much still being written. We’re excited to see what future iterations on token distributions emerge. If you’re thinking about creative ways to incorporate/distribute tokens into what you’re building, we’d love to hear from you.

Thank you to Nathan Schneider, Joel Monegro, Liam Horne, Jackson Dahl, Jacob Horne, Chris Dixon, Fred Wilson, Mario Laul, Ben Leventhal, Joey Santoro, Scott Moore, David Phelps, Benny Giang, Lakshman Sankar, Henri Stern, Cooper Turley and Variant team members Caleb Shough, Alana Levin, Geoff Hamilton, and Jack Gorman for feedback that strengthened this piece.

If you’d like to work on projects building in this space, fill out our talent form.

+++

This post is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any investment and should not be used in the evaluation of the merits of making any investment decision. It should not be relied upon for accounting, legal or tax advice or investment recommendations. You should consult your own advisers as to legal, business, tax, and other related matters concerning any investment. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by Variant. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, Variant has not independently verified such information. Variant makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. This post reflects the current opinions of the authors and is not made on behalf of Variant or its Clients and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Variant, its General Partners, its affiliates, advisors or individuals associated with Variant. The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without being updated.

Variant is an investor in Zora.