Daniel Barabander

Thoughts on the Law of Insider Trading and Prediction Markets

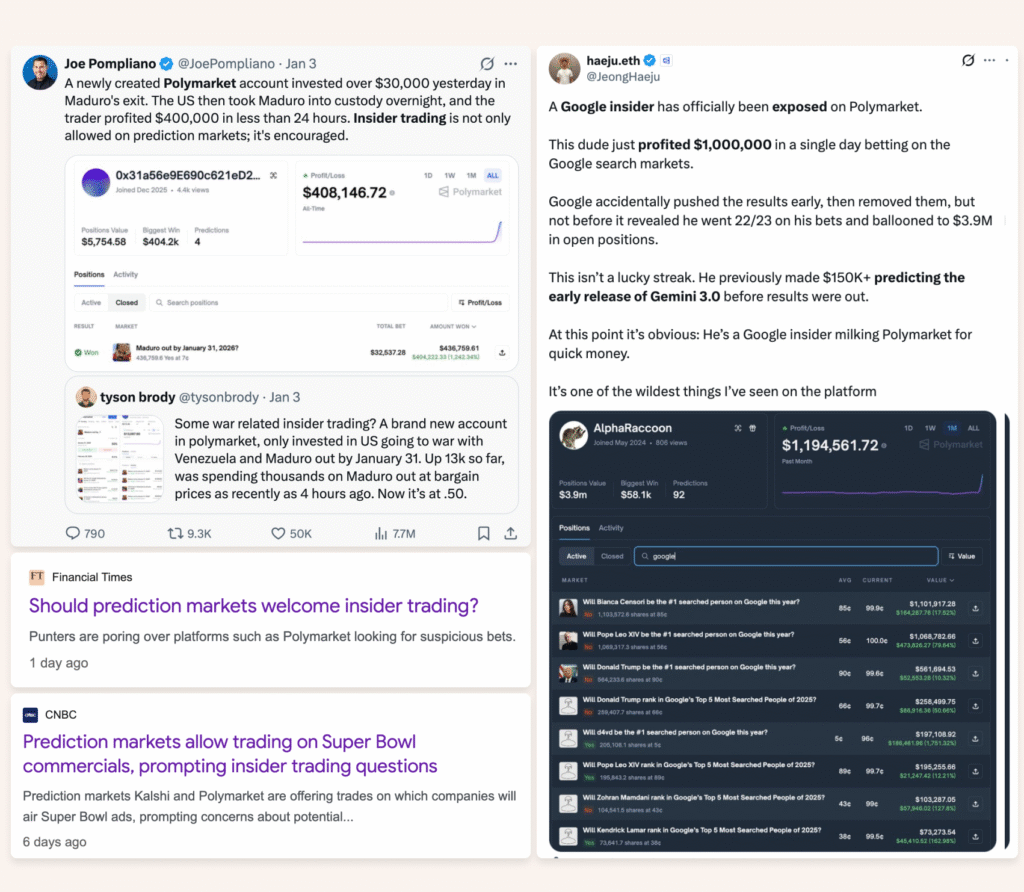

Insider trading in prediction markets has become a hot topic recently.

Founders see wallets popping up out of nowhere to trade ahead of major events and naturally ask whether something illegal is happening. Answering that question, however, requires stepping back and understanding how insider trading law actually works. Most people don’t.

When you ask most lawyers about insider trading, you get a lot of legal mumbo jumbo. You’ll hear about “duties,” the “classical theory,” the “misappropriation theory,” “tippers,” “tippees,” “insiders,” “outsiders,” and on and on. Their brains start to combust when applying this to a novel area like prediction markets.

While this is definitely not legal advice (and you should speak to your lawyer), I want to give a simplified framework for how I think about insider trading law generally, and how I think it applies to prediction markets.

Insider Trading = A Type of Fraud

The first thing you must understand about insider trading is that the law treats it as a form of fraud. Like all fraud, insider trading involves deception for personal gain. That deception typically arises from breaking an implicit or explicit promise about how information entrusted for a limited purpose may be used. There is no “insider trading rule,” just anti-fraud rules that have been applied to insider trading. The major difference between insider trading as a form of fraud and what we typically think of as fraud is that in the former, the promises can feel much subtler and are therefore easier to break.

The canonical way insider trading occurs is when an employee1 breaches a promise to their employer by trading on material non-public information (MNPI) in their company’s stock. Whether you like it or not, if you work for a company, you have an implied promise (set in law) to act in the best interests of that company and its shareholders. That promise is likely even specifically outlined in the employee handbook you agreed to comply with when you joined the company. When an employee trades on MNPI by buying or selling the company’s stock, there is an information asymmetry with the shareholder on the other side of the trade; transacting on that asymmetry constitutes a deceptive breach of the promise to that shareholder.2

The thing I see people miss is that this example is merely one flavor of insider trading. Any time someone deceptively breaches an implied or express promise in connection with a trade, insider trading may be in play.

For example, imagine an employee who learns of an M&A transaction involving their company. Knowing the canonical insider trading scenario is not kosher, the employee tries to be clever and uses this MNPI to purchase shares of the company’s biggest competitor, believing its stock will skyrocket on the news. Even though the employee has no implied promise to act in the best interests of the competitor’s shareholders, this may still be insider trading.3 Why? Because the employee made a promise to their own company — whether through company policies, a confidentiality agreement, or simply by virtue of their implied promise to act in its best interest — to use confidential information only for legitimate business purposes. Using that information for personal trading in a competitor’s stock is not that. The employee has therefore arguably breached a promise deceptively and engaged in insider trading.

The Promise Is the Point

The promise is key. Consider a person who overhears two investment bankers at a nearby table loudly discussing a pending M&A transaction while out to lunch. The person recognizes the target, leaves the restaurant, and trades in the company’s stock before the deal is announced. Even though the information is clearly MNPI, this is generally not insider trading. The trader did not make any express or implied promise to the bankers to keep news of the M&A transaction confidential and has no implied promise to the company or its shareholders. The bankers themselves may have violated their own obligations by speaking carelessly in public, but absent a deceptive breach of a duty by the trader, there is no fraud — and therefore no insider trading.

Any time someone deceptively breaches an implied or express promise in connection with a trade, insider trading may be in play.

Understood in terms of deceptively breaking promises, we can correct the common misconception that insider trading is limited to securities.4 To the contrary, analogous concerns can arise in commodities markets, including derivatives.5 A derivatives trader at Cargill who, as part of their job, learns the firm is about to make a large purchase of wheat and then trades ahead of that purchase in the wheat futures market in their personal account is likely engaging in insider trading. In that case, the trader has deceptively breached promises made to their employer — through company policies, confidentiality agreements, or simply by virtue of their role — about how confidential information may be used, namely, only for Cargill’s purposes. By contrast, if that same trader executes trades ahead of the purchase on Cargill’s behalf, as part of their assigned role, this is not insider trading. Even though the trader is acting on MNPI (i.e., knowledge of Cargill’s planned market trades), there is no deceptive breach of a promise: the trader has no implied duty to other futures traders, and trading on that information is precisely what they are authorized to do for their employer.

The Law Applies to Prediction Markets, Too

So how does this change things for prediction market traders? My core point is probably disappointing in its mundanity: nothing about the law changes. Fraud is fraud, and the rules are flexible. The relevant question is still whether the trader is deceptively breaching a promise by making the trade.

Accordingly, a Tesla employee with access to Q4 financials is likely engaging in insider trading if they use that information to trade on a “Will TSLA beat Q4 estimates?” prediction market. The insider trading occurs either because the employee has breached a promise to Tesla shareholders6 or has violated a confidentiality or other agreement restricting the use of the company’s confidential information for personal gain. But let’s say that same employee instead trades on a prediction market asking, “Will U.S. EV charging demand grow faster than gasoline demand over the next two years?” As long as they use publicly available EV adoption data and general industry expertise developed over years at Tesla — rather than Tesla’s internal plans — it is likely not insider trading, because no confidential information was misused and no promise was breached.

What prediction markets will do, however, is push the law to its limits and test whether it bends or breaks. Traditional markets are typically tied to a company. In securities, the tie to a company is direct (e.g., Tesla’s Q4 performance). In commodities, it is indirect (e.g., Cargill’s large wheat purchase). That matters because companies are often the source of promises to keep information confidential and/or use information only for business purposes — and those are the promises that give rise to insider trading liability, whether implied by law or made explicit through confidentiality agreements, policies, or similar constraints.

By widening the aperture to make almost anything tradable, prediction markets expand the sources of valuable inside information — often into contexts where the existence of any relevant promise is far less clear. This is especially true for permissionless or opinion markets, which often have no relevant company at all.

As just one example, imagine a prediction market at a local high school asking, “Who will be Prom King?” Suppose your friend is the most popular person in the class and tells you he won’t be able to attend prom. If you trade on that information, is it insider trading? The legal question would still be whether you deceptively breached a promise, but in this setting, any such promise would have to be implied from your relationship or the circumstances of the disclosure, rather than from a clear duty to a company or a formal agreement. That makes litigating insider trading significantly more difficult.

It gets very fuzzy, very fast.7

Thank you to my builder friends Adhi Rajaprabhakaran, John Wang, Ella Papanek, and Matt Liston for their thoughtful feedback on this article.

Thank you to my legal friends Justin Browder, Mike Frisch, Jason Gottlieb, and Zack Shapiro for their thoughtful feedback on this article.

Footnotes

1. By the way, courts have also repeatedly held that this implied promise can transfer to someone outside the company if they receive MNPI from an employee who disclosed it for personal benefit, and the recipient knows or should know that the disclosure breached this promise — this is the infamous “tipping” liability.

2. The logic is that, as part of acting in the shareholder’s best interest, the employee has a responsibility to not to misappropriate confidential company information. The employee is required to protect that information, both as a fiduciary and as a matter of internal policy. Failing to do so is treated as a deceptive breach of this promise, and thus, fraud (called insider trading).

3. However, I must caveat that this example is based on a real case, SEC v. Panuwat, which is a hot topic right now and subject to a lot of debate on whether this is fairly insider trading.

4. My legal readers will reasonably object that “insider trading” is an awkward label in commodities markets. As previous Commissioner Caroline Pham has emphasized, commodities law does not turn on issuer-centric (i.e., “insider”) concepts like MNPI, and importing securities-law terminology risks doctrinal confusion. That critique is well taken. But if the objective is preventing fraud and deceptive trading, the core concern survives even when the market is not a securities market.

5. This doesn’t mean the nature of the underlying market is irrelevant — it can matter a great deal for how insider trading is enforced. If the underlying event or outcome is a security, the SEC would likely have jurisdiction; if it is a commodity or a commodity interest, jurisdiction would generally lie with the CFTC. And if the market involves a security, private plaintiffs — often through class actions — may also have a right to sue, whereas it is far less clear whether a comparable private right of action exists for commodities.

6. Courts have made clear that it does not matter that a binary option rather than the underlying stock is being traded because the economic substance of the exposure is the same.

7. To be clear, anytime someone commits fraud, the government has many other tools at its disposal to prosecute bad actors besides insider trading law — including criminal wire fraud. The government is not just going to throw up its hands around legal formalism, and will try and find a legal theory to punish behavior that it views as harming people. We saw this in the OpenSea insider trading case (Chastain), where the DOJ brought charges under the wire fraud statute, likely to avoid litigating whether NFTs were securities. So this fuzziness is not a window to commit fraud.

All information contained herein is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any investment and should not be used in the evaluation of the merits of making any investment decision. It should not be relied upon for accounting, legal or tax advice or investment recommendations. You should consult your own advisers as to legal, business, tax, and other related matters concerning any investment. None of the opinions or positions provided herein are intended to be treated as legal advice or to create an attorney-client relationship. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by Variant. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, Variant has not independently verified such information. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by Variant, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Variant (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for Variant to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://variant.fund/portfolio. Variant makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. This post reflects the current opinions of the authors and is not made on behalf of Variant or its Clients and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Variant, its General Partners, its affiliates, advisors or individuals associated with Variant. The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without being updated. All liability with respect to actions taken or not taken based on the contents of the information contained herein are hereby expressly disclaimed. The content of this post is provided “as is;” no representations are made that the content is error-free.