Elijah Fox

We Are Not Onboarding Institutions (for Now)

The implications of deleveraging on derivatives exchanges in traditional finance and crypto

In this world I will bind myself… to serve and wait on you; When we meet in the next world wages will fall due.

– The Devil to Faust

Summary

- Today’s crypto derivatives exchanges (on and offchain) are not designed for institutions. They prioritize high leverage (which appeals to retail) over limiting tail risks (which appeals to institutions).

- While there are barriers to onchain exchanges moving towards institutional-grade risk management (e.g., from a lack of offchain recourse), significant improvements can easily be made if the exchange puts skin in the game (with its own capital acting as a buffer). There may be other more creative mitigations as well, which are briefly discussed in the conclusion.

- Even if onchain exchanges choose not to build for institutions, open-source protocols for deleveraging are in many ways still better for retail traders than opaque, ad-hoc, centralized deleveraging mechanisms (e.g., Robinhood during the GME pump).

Introduction

It’s no secret that crypto traders love leverage.

The exchanges we trade on understand this and service the demand. But a tension exists: the more leverage an exchange offers, the more losses are amplified and the less collateral there is to cover them. As a result, there’s a greater risk of insolvency.

Insolvencies must be avoided at all costs though. If an exchange can’t honor withdrawals, it’s screwed. No one will ever use it again. So a compromise needs to be found that reduces this risk without sacrificing the leverage that makes an exchange attractive to users.

We saw the consequences of this very recently. On October 10th, the entire crypto market plummeted in value with haste. To protect against insolvency, auto-deleveraging (ADL) kicked in. This is where profitable positions are forcibly closed at worse prices than market in order to cover and close corresponding, unprofitable, insolvent positions. At the expense of these profitable traders, the exchanges remained solvent.

Framed as a compromise between traders who want significant leverage and exchanges who don’t want to bear the risks, this isn’t particularly a problem. It’s just a strategic move where both parties get what they want. The exchange can keep customers happy while avoiding losses or having to close down entirely.

Where things get problematic is in the ability of these exchanges to onboard a different profile of traders: the coveted “institutions.”

Loosely defined, institutions are businesses with lots of capital and orderflow who are used to trading derivatives on US-regulated exchanges. On these exchanges, leverage is capped, and auto-deleveraging is a last resort; it is first buffered by billions of dollars of well-defined insurance. The tail risk of covering someone else’s insolvency might not matter when you’re shooting for 100x, but it does when you’re just trying to beat 1.04x annually.

Why does this matter?

As the industry gets bigger, the exchanges we trade on want to grow with it. But the existing set of crypto traders to onboard is capped in size. So exchanges must look elsewhere for growth.

There are merits to striving towards this. Programmable, verifiable, self-custodial finance is a zero-to-one unlock. It enables new ways to trade and compose financial instruments. And it does so in a way that’s more transparent and (in the limit) more trustworthy. It makes sense that the next wave of growth will come from bringing these advantages to the traditional system.

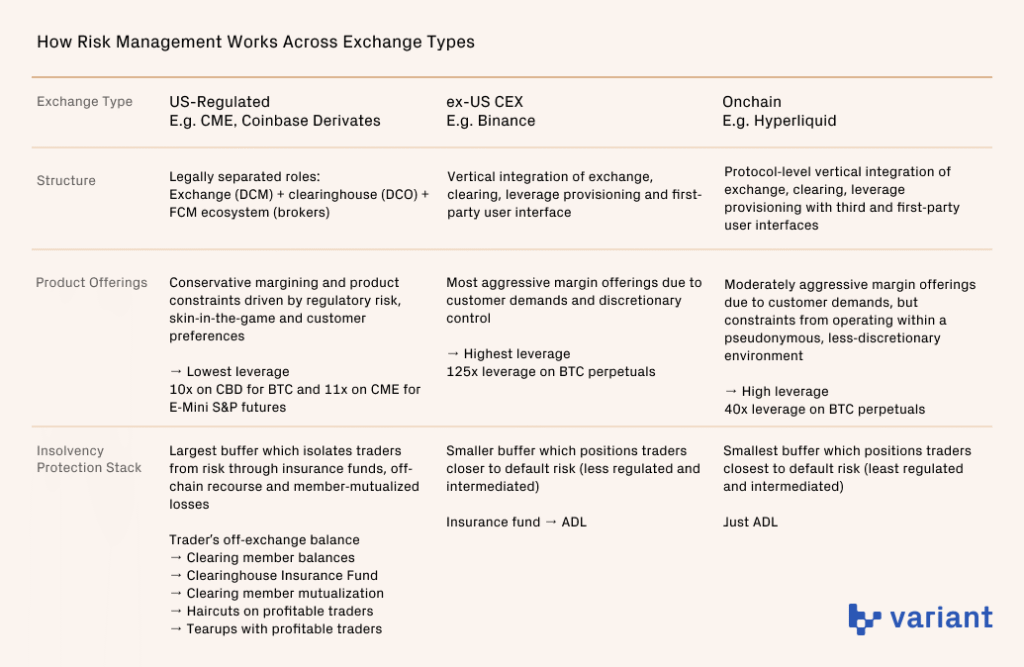

But to get the chance to onboard these users, we need to create systems that manage risk in line with their preferences. To better assess what needs to be done, we first have to unpack how risk management, especially surrounding insolvency, works in traditional finance and how it differs from crypto exchanges.1

While there has been a lot of reflection about deleveraging on crypto exchanges, most of the discussion has been about designing better ADL mechanisms. This is useful but misses a higher-order question. Attention also needs to be given to why deleveraging works differently in crypto in the first place and what to do about it moving forward.

Deleveraging in Traditional Finance

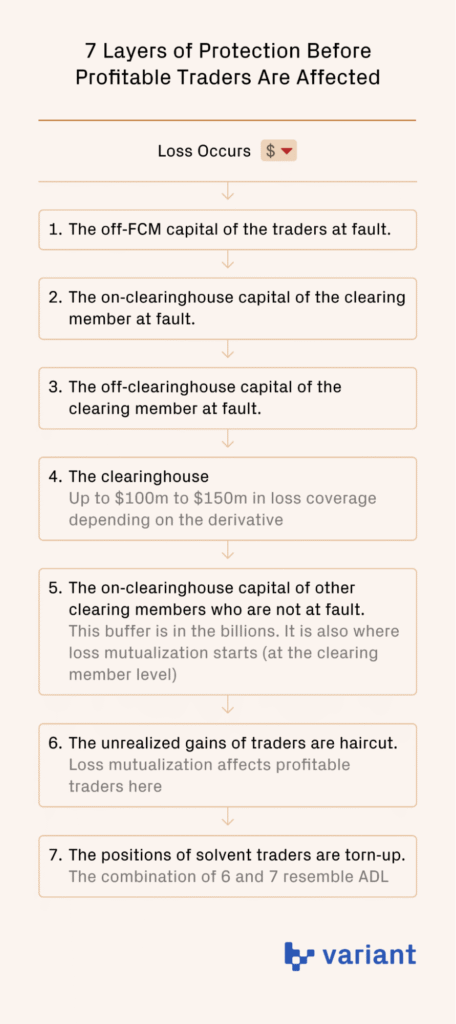

Whereas tear-ups and haircuts are the first line of defense against insolvency on crypto derivative exchanges, they are the last line of defense on traditional derivative exchanges.

For example, on the CME, the “exchange” takes on the immediate costs of insolvent positions through a “waterfall” that determines which market participants take on which risks in what order.

Notably, however, the “exchange” in this setting is not a single integrated venue like it is in crypto. Instead, the roles of leverage provisioning and trade settlement are modularized into separate functions: the clearing members and the clearinghouse.

The clearing members, aka Clearing Futures Commission Merchants (clearing FCMs), are well-capitalized and well-regulated institutions (like banks) that serve as the primary interface for users — they are leverage provisioners that custody users’ collateral. Clearing members access the exchange on behalf of their clients by holding accounts at the clearinghouse, the entity responsible for settling trades. After an order is matched on an exchange, the clearinghouse inserts itself between counterparties to settle, becoming the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer.

Unlike in crypto, where there is little to no buffer before profitable traders are impacted by insolvent ones, the clearing members and clearinghouse provide a considerable buffer through a waterfall mechanism that protects solvent traders from bearing the costs of their peers. Under the CME’s waterfall, the order for covering losses is:

What stands out is how differently two systems with apparently similar goals treat the same scenario. Whereas the CME provides billions of dollars of buffers before profitable positions are affected, most crypto derivative exchanges provide little to none.

Market Design Motivations

So naturally, the question is why?

Reason #1: Target audience and Incentives

Crypto retail seems to care much more about accessing a lot of leverage than about the risk of ADL. And since leverage increases the risk of insolvency, exchanges would be less inclined to offer the high leverage that retail demands if they had to cover insolvencies.

In contrast, institutions care deeply about the tail risks associated with their positions. If every shortfall is going to affect their positions, they’ll likely refuse to use the exchange. For example, consider a hedge fund running a delta-neutral strategy, with the short leg of its trade taking place on a perps exchange. If ADL is triggered, its long positions are left naked without a proper hedge. It’s not necessarily important for traders hedging risk to be able to be 125x leveraged, but it is important to be reliably protected, even in extreme scenarios. As such, they’ll shy away from using exchanges that take on additional risk to service a market of users they don’t care to be on the same exchange with.2

The conclusion is that crypto derivatives exchanges seeking to onboard institutions will need to reconsider their policies. And while a thin buffer and high available leverage are at odds with the stated goal of building the future of institutional finance, they are not at odds with what much of retail is seeking. So, ultimately, the risk an exchange offers is downstream of who it is trying to onboard.

Reason #2: Pseudonymous environments

A second reason is that the waterfall is naturally thinned by the lack of recourse that’s possible in a pseudonymous, onchain environment. On the CME, clearing members can collect additional margin from traders if their losses aren’t fully covered, and the clearinghouse can collect additional margin from clearing members if its losses aren’t fully covered.

Now, try collecting off-exchange funds from a self-custodied wallet you identify by its hexadecimal. You just can’t!

Without the ability to rely on off-exchange recourse, the buffer created by traders and clearing members disappears. The only thing standing between insolvency and the deleveraging of solvent traders is whatever the protocol has reserved as insurance. The lack of any buffer also discourages exchanges from putting funds at immediate risk since they are left at the top of any waterfall.

This is only a fundamental blocker for exchanges with pseudonymous accounts. Onchain or offchain exchanges that position themselves to be able to take off-exchange recourse can still use these levers to increase the buffer before loss-mutualization kicks in.3

All that said, for some traders this is actually desirable. Since their potential losses are capped to the collateral value they provide to the exchange, they are able to isolate their risk. But although this is the default for onchain exchanges, it isn’t exclusive to crypto: traders can still negotiate agreements with their brokers on exchanges within the traditional financial system as well.

It’s Not So Bad (for Retail)

But it isn’t all doom and gloom. Optimizing for retail isn’t inherently bad. And at the least, when it’s done onchain and open-sourced, deleveraging can be transparent and will credibly follow any established rules.

This is not the case for every retail trading venue. Here are two relevant examples:

Robinhood after GME pumped

The most notorious case of an opaque, ad-hoc deleveraging event was what took place on Robinhood after meme stocks like GME quickly jumped in price. Since equities don’t settle instantly, Robinhood operates as a clearing member of a clearinghouse known as the National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC), which is tasked with managing the risk that settlement can’t be completed if a counterparty fails. Similar to clearing members of the CME, clearing members of the NSCC must post margin in proportion to their unsettled positions.

When Robinhood users continued to heavily buy throughout the pump, Robinhood’s unsettled balance ballooned. In response, the NSCC significantly increased Robinhood’s margin requirements to ensure it had the capital to settle the buy orders. But this risked creating liquidity issues for Robinhood. If their unsettled balance continued to grow from continued buying, Robinhood would eventually not have enough capital to meet the NSCC’s new margin requirements. To reduce its risk and net out the unsettled buy orders, during peak price action, Robinhood notoriously turned off retail’s ability to keep buying these stocks. This left users with no choice but to sell (and consequently reduce Robinhood’s unsettled balance).

This highlights two issues with Robinhood’s model:

- The use of an ad-hoc mechanism for deleveraging: Without knowing that Robinhood would halt buying, traders couldn’t position themselves to avoid losses.

- T+2 day settlement: The longer settlement times are, the more unsettled balances can build up. This increases settlement risk and leads to liquidity constraints when the clearinghouse (NSCC) calls additional capital. In the aftermath of Robinhood’s incident, the SEC reduced settlement to T+1 day.

Crypto CEXs on 10/10

In the aftermath of 10/10, rumors circulated on X [1, 2] that some trading entities had side agreements with the exchanges they trade on to prevent their positions from being ADL’d. If this is true, traders without these agreements were unfairly prioritized for forced closure, putting them at a major, opaque disadvantage. Whether or not these trading firms actually received explicit ADL protection, the episode underscores a problem with transparency and incentives in centralized crypto exchanges.

Unlike many exchanges, Binance at least ate into $188m of its $1.23b insurance fund before triggering ADL. But the size of its insurance buffer wasn’t made public ahead of time.4 To be fair, Binance may have legitimate security concerns around how adversarial traders can abuse this knowledge. Regardless, this level of transparency may still be short of what a large institution requires or is used to.

Mitigating these issues by building onchain. Building onchain is an alternative to using a trusted third party to ensure deleveraging conditions are transparent and credibly followed. When onchain is used alongside open source:

- The rules for deleveraging must be specified ahead of time in order for nodes to participate in consensus.

- T+1 settlement is replaced by near-instant settlement based on how quickly the protocol finalizes.

Conclusion

Most of today’s crypto exchanges were not designed with institutional adoption in mind. They prioritize offering high leverage at the expense of increasing the risk of forced position closure and loss-mutualization. While this is an attractive tradeoff for retail traders, it inhibits exchanges’ ability to onboard institutional capital.

That said, while there are some difficulties with onchain exchanges moving towards institutional-grade risk management (e.g., from a lack of offchain recourse), significant improvements could easily be made by reducing maximum leverage and providing greater capital buffers before ADL. This hints at a world with different onchain derivatives exchanges tailored to different classes of users. For example, the onchain exchanges that prioritize institutions can build insurance mechanisms that put skin in the game and leverage caps that reduce the risk they need to pay out. Notably, we are already seeing diversification play out with offchain crypto derivatives, where the CME, Coinbase, Hyperliquid, and Binance are all addressing different audiences via different architectures and risk management practices.

There may also be less-obvious mitigations worth exploring. For example, one could imagine an optional broker layer (~clearing members) that traders interface with for increased leverage or protections. In this setup, the exchange itself would still offer some leverage and protection, but push the fine-tuning outwards. Specialized brokers would fill in any gaps, granting additional leverage, protection, or flexibility desired by traders. This could include features which support margin calls as an alternative to automatic liquidations. In some ways this already exists for off-exchange leverage by composing lend-borrow protocols with a perpetual account (e.g., a user on Hyperliquid can borrow USDC from a money market and atomically use it to trade perps).

And even if onchain exchanges choose not to build for institutions, there are still reasons to be excited. Open-source, onchain exchanges are a useful alternative to opaque, centralized deleveraging mechanics. On the former, a trader can both understand how an exchange is supposed to work in theory and trust that the onchain instance will work the way the code was written. As a result, traders can better position themselves to manage risk and avoid surprises.

Thank you to Salah (Variant), Daniel (Variant), the entire Derive team, Aaron (Felix), Dan (Nascent), Mustafa (Volt), Austin (Whetstone Labs), Ceteris (Delphi), Mr Plumpkin (Variational)

Footnotes

1. Throughout the post, we use ”crypto exchanges” to describe crypto derivatives exchanges that don’t operate within the United States regulatory frameworks for derivatives exchanges. Coinbase Derivatives is technically not included when we use “crypto exchanges” to describe this category since it operates with the proper US licenses.

2. There are some “institutions” that are willing to trade on crypto derivatives exchanges, namely, firms that trade at higher frequencies. Their willingness comes from their motivation — they are not trading to manage risk or express a longer-term view about the direction of the market, they are trading to capture value from the inefficiencies that less informed retail traders create.

3. It is worth noting that the operational and legal friction with calling off-exchange assets from insolvent traders make it expensive, unreliable and time-intensive to do.

4. Per Binance’s insurance fund policy, “The multiplier for each insurance fund is pre-determined and confidential due to risk management considerations.”

All information contained herein is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any investment and should not be used in the evaluation of the merits of making any investment decision. It should not be relied upon for accounting, legal or tax advice or investment recommendations. You should consult your own advisers as to legal, business, tax, and other related matters concerning any investment. None of the opinions or positions provided herein are intended to be treated as legal advice or to create an attorney-client relationship. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by Variant. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, Variant has not independently verified such information. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by Variant, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Variant (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for Variant to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://variant.fund/portfolio. Variant makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. This post reflects the current opinions of the authors and is not made on behalf of Variant or its Clients and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Variant, its General Partners, its affiliates, advisors or individuals associated with Variant. The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without being updated. All liability with respect to actions taken or not taken based on the contents of the information contained herein are hereby expressly disclaimed. The content of this post is provided “as is;” no representations are made that the content is error-free.